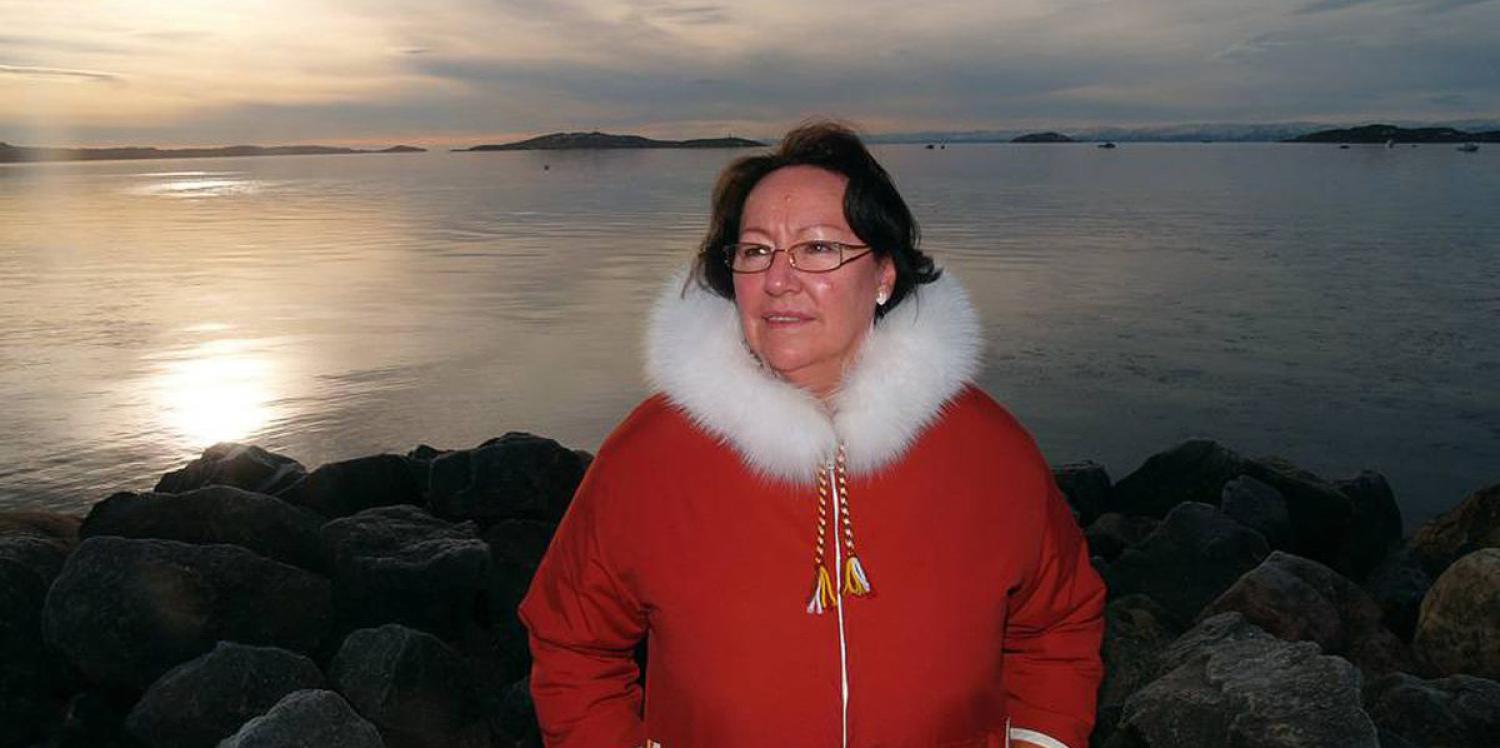

On Dec. 7, 2005, Canadian-born mother and grandmother Sheila Watt-Cloutier filed a 163-page petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights arguing that the impacts of climate change violated the ãfundamental human rightsã of Indigenous Inuit people like her across the Arctic.

ãIt is the responsibility of the United States, as the largest source of greenhouse gases, to take immediate and effective action to protect the human rights of the Inuit,ã the petition read.ä»The commission ultimately declined to hear the case.

But Watt-Cloutierãs bold move helped kick-start what many describe as a sea change in how the international community thinks about climate change. Rather than center conversations around the science behind it or the babyøÝýËapps and politics of addressing it, as had been the norm for decades, Watt-Cloutier and a new brand of climate justice advocates took a different approach.ä»They framed climate change not as a distant, abstract concern but as a current human rights crisis that disproportionately impacts marginalized communities. Thus, they made the case that government and industry are duty-bound to respect and protect those rights in the face of climate change.

ãBefore that time, at nearly every meeting I attended, they were talking about polar bears and ice,ã said Cloutier, who will present a keynote speech at the upcoming Right Here, Right Now Global Climate Summit on the CU Boulder campus. ãTo put a human face to the issue was really important.ã

Two years later, a small group of island states led by the Maldives joined forces to adopt theä»Malûˋ Declaration, the first intergovernmental statement that ãclimate change has clear and immediate implications for the full enjoyment of human rights.ã The next year, the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted the first of what became a series of resolutions linking climate change to human rights.

In February 2020, UN Secretary General Antû°nio Guterres proclaimed unequivocally:ä»ãThe climate crisis is the biggest threat to our survival as a species and is already threatening human rights around the world.ã

In framing it this way, climate justice advocates say they gain more leverage in both the court of public opinion and the court of law, and better assure that as policymakers set out to craft solutions, those most affected by climate change (but often least responsible for it) have a seat at the table.

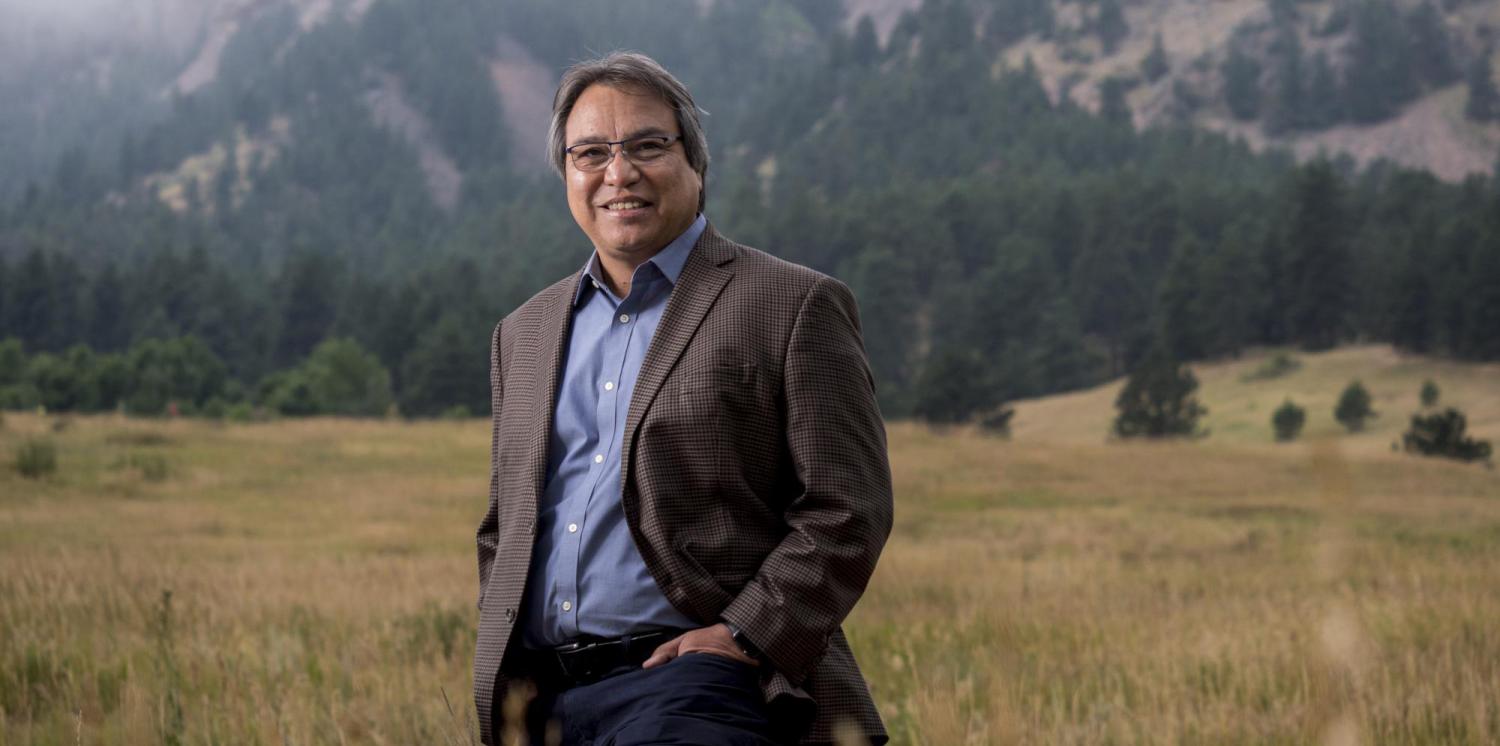

ãViewing climate change through a human rights lens brings to the fore the urgency of the problem and helps us to focus on what it is really aboutãhuman beings and our survival,ã said James Anaya, a university Distinguished Professor and professor of international law at CU Boulder, and the lead of three co-chairs for the climate summit.

The toll on human rights

In 1948, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which guarantees that all human beings are entitled to a social and international order in which their rights and freedoms can be fully realized.

Those rights include the right to health, food, housing, life and culture.

Climate change threatens all of them, and the Indigenous people of the Arctic, which has warmed much faster than any other region of the globe, were among the first to feel it, Watt-Cloutier explained.

In the village of Shishmaref, Alaska, where people have been living, hunting and fishing for 2,000 years, melting sea ice is swallowing homes. Roads built on once-sturdy permafrost are sinking as it thaws. Hunters who have traveled across the ice for centuries now face the danger of breaking through it. Seals and polar bears that depend on the ice are moving farther out, threatening food supplies. Thinning ozone and increased ultraviolet exposure have boosted reports of skin cancer and cataracts.

Erosion next to houses in Shishmaref, Alaska

Aerial view of Shishmaref, Alaska

ãWe are the most adaptable people in the world. We invented the kayak. We can build a home made of snow that is warm enough for a mother to birth in. We are teachers, not victims. I believe Indigenous wisdom is the medicine the world seeks.ã

Inuit culture is also under threat, said Watt-Cloutier, as hunting traditions in the Arctic come with key lessons about resiliency, coping, patience and boldness.

ãOur culture is based on the ice, the snow and the cold. That's who we are,ã said Watt -Cloutier, author of The Right to Be Cold: One Womanãs Fight to Protect the Arctic and Save the Planet from Climate Change.

Elsewhere around the globe, the human toll of climate change became apparent to Mary Robinson, then the UN high commissioner for human rights in the early 2000s.ä»ãNo matter where I went, I kept hearing variations on the same phrase: ãBut things are so much worse now,ãã she wrote in her 2019 bestseller, Climate Justice: Hope, Resilience and the Fight for a Sustainable Future.

Robinson, the former president of Ireland, who will deliver a keynote speech at the climate summit in Boulder, recalls farmers in Africa whose harvests failed to arrive or whose crops and villages were washed away by floods.

ãIn the past, I had seen images of stranded polar bears and the disappearance of ancient glaciers, but these stories from the frontlines of climate change suddenly began to match the scientific findings I was reading about,ã Robinson wrote.

Anaya is quick to note that while the ravages of climate change are now being felt globallyãincluding in Boulder, which has been hit by devastating floods and fires in recent yearsãwomen, people with disabilities, Indigenous peoples, children and other marginalized groups tend to feel the brunt.

ãA human rights approach pays attention to those groups that are particularly in vulnerable situations and makes sure to include their voices in the discussions about solutions,ã Anaya said.ä»

Obligations and solutions

Under international human rights law, governments have the primary obligation to protect human rights, Anaya said.

Increasingly, climate justice advocates are seizing upon this legal obligation and taking governments to court for failure to protect human rights.

For instance, in 2013, the Urgenda Foundation filed a lawsuit against the Dutch government demanding that it take steps to address the toll climate change was taking on human rights. In a groundbreaking 2019 decision, the Supreme Court of the Netherlands ordered the government to cut the nationãs greenhouse gas emissions by 25% from 1990 levels.

Since then, hundreds of plaintiffs have filed suit against governments and businesses for failing to protect human rights from the impacts of climate change.

Meanwhile, a human rights approach has given a new voice to vulnerable communities, aiming to ensure that when solutions are discussed, their interests are top of mind.

ãThese solutions have to be equitable, and certain groups should not bear the cost more than others,ã Anaya said.

For instance, if wind power is a solution, how will the construction of those wind farms affect the lives, livelihoods and traditions of people in local communities? When it comes to costly mitigation and adaptation strategies, who will pay?

ãThe human rights framing emphasizes equity and fairness. Those who are most responsible for climate change have the greatest responsibility to address it,ã Anaya said.

Watt-Cloutier is quick to note that those who are most vulnerable to climate changeãwhile often portrayed as victims and left unheardãtend to have unique and valuable perspectives on solutions.

ãWe are the most adaptable people in the world. We invented the kayak. We can build a home made of snow that is warm enough for a mother to birth in. We are teachers, not victims,ã she said of the Inuit. ãI believe Indigenous wisdom is the medicine the world seeks.ã

As the world increasingly seeks an answer to what is now broadly viewed as an existential threat to human rights and the future of humanity, she said she has renewed hope.

ãI believe the campaigns that link climate change to human rights protection efforts, that acknowledge our shared humanity and our shared future, are the most effective way to bring about lasting change.ã